The importance of irony and satire in helplessness and tragedy

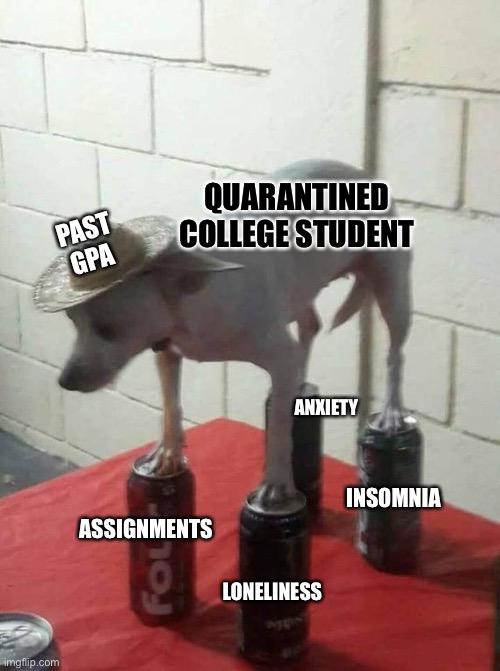

A good laugh helps to get through hard times. It is often perceived and used as a coping mechanism to make the weight of reality feel just a bit lighter. [Today, one of the ways through which we witness irony and satire is memes, especially while the Covid-19 pandemic spreads across the world (refer to Image 1 for an example made by me on the current situation in order to get through it).]

However, when irony and satire is found in films and books, such as Elia Suleiman’s The time hat remains and Emile Habibi’s The secret life of Saeed: The pessoptimist, it takes coping with a sense of helplessness to another level. It makes room for a whole new experience, making the viewer or the reader appreciate the story and the struggles within. In particular, I noticed Suleiman’s use of irony through a careful use of theater-like scenography and choreographys, while I noticed both Habibi and Suleiman’s satire in taking the main characters out of the main storyline (in different ways), to highlight the helplessness of the characters in their context.

Irony and Suleiman’s work

In The time that remains, Suleiman sets up the whole film as it was a theater performance, starting from the overall film structure to carefully composed shots and choreographys, and I believe he does this to highlight how surreal moments of struggle can feel once you experience them personally. The film is virtually divided into four different “acts”. The first illustrates the story of Elia’s (the main character) father’s young years as arm maker in the conflict between Palestine and Israel. The second “act” focuses on Elia’s childhood, and how his teachers reprimanded him for proposing ideas against the USA in school. The third act follows Elia’s young adulthood, where he starts to act in ways that get the attention of the local authorities, who force him to leave his country. The fourth act focuses on Elia’s late adulthood, as he comes back home and deals with what is left of his family and his country.

I believe this choice of dividing the film into a four-act piece is strongly ties to the way some of the sequences on the film are performed. Indeed, especially when a grave moment was about to happen in the plot, carefully designed dances (or what seemed like it) took place to make the content of the narrative more bearable to the viewer. For instance, at the beginning of the film, Iranian soldiers start emptying houses of their objects, after their residents were made to leave the town, an act that is chilling and uncomfortable, but that is carried out through diegetic music and what looked like a dance among the soldiers, which made the scene much more powerful.

Satire in Habibi and Suleiman: stepping out of the narrative

I believe that one of the elements that I found the most interesting in both the film and the book, that I believe was used as a device of satire as a “defence mechanism” against the weight of the reality, was the ability for the characters to step out of the narrative, thought they were supposed to be the main characters in the stories that were seen and read. Indeed, Elia’s character does not speak throughout the film, he becomes a sort of external witness to his own story, without being able to change much of the events that happen around him, including helplessly looking at the conflict in his motherland and at the loss of his parents.

In Habibi’s book, though differently, Saeed acts in similar ways that make him step out of his own narrative, even if only in his mind and in a more explicit way for the reader. Saeed often mentions his encounter with extraterrestrials, and how he was taken by them, even he welcomed with glee. Indeed, Saeed reminds the reader that he had always wished to disappear. Additionally, when he crosses the border to Israel, he is in the car of a doctor affiliated with the Arab Salvation Army. He travels away, again stepping out of his own narrative, also because the doctor seemed to fancy Saeed’s sister, and the doctor would have liked him out of his way while pursuing the relationship.

I believe that this aspect of distancing themselves from their own story, while still being part of it, leaves a tribute to the sense of helplessness that they might have felt in real life during those years, leaving the viewer or reader to reflect of the weight of this feeling.

Sources:

Habibi, E. (2010). The secret life of Saeed, the pessoptimist. Arabia Books.

Image 1: Imgflip.com and Giulia Villanucci